THE SLEEPING PLACE Susie Campbell/Rose Ferraby from Guillemot Press.

(Pre-orders here https://www.guillemotpress.co.uk/poetry/susie-campbell-the-sleeping-place)

It is here! My author copies of THE SLEEPING PLACE arrived this week. The book is everything I had envisioned and more. Because I had worked previously with Guillemot Press and artist/archaeologist Rose Ferraby, I was able to draw on my knowledge of what they could bring to the realisation of this project if I were fortunate enough to be published by them again. And I built this into my vision of THE SLEEPING PLACE, dreaming of a book as multi-layered as the archaeological excavations it depicts. In the hope that Guillemot and Rose would come on board, I imagined a book whose design and visual artwork would work in an assemblage with the text itself. I am so excited that this imaginary book is now a real book to share with a wider audience.

Cover of THE SLEEPING PLACE with detail from Rose Ferraby’s artwork plus pieces of chalk picked up from the site.

Early in my discovery that an ancient Saxon burial ground had been excavated beneath the site of my family home, I had the first conversation in what would become a series of formative chats with Rose about art and archeology. We talked about the importance of broadening the archaeological record to include a range of responses to the material traces of the past. These responses might include visual art or a range of other art forms. Poetry of course is one of these forms. I am fascinated by the poetry of archaeology. There is much important work currently being done, including volumes of poetry (Vestiges and Peat) curated by poet archaeologist Melanie Giles with artwork by Rose. Other important books engaging with poetry, archaeology and the landscape are currently being published by Corbel Stone Press, Longbarrow Press and recently, Osmosis Press, as well as other books by Guillemot Press and many other presses producing important work in this field. Rose is of course renowned for her archaeological artwork, including her work on Seahenge for the recent British Museum Stonehenge exhibition (https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/art-seahenge). It was an enormous privilege to collaborate with her on this project. Her collage work for THE SLEEPING PLACE not only adds another rich layer to the book, image and text working together, but also creates new spaces for the reader’s creative response to the landscape. And, as always, Rose’s work brings an intelligent integrity, compassion and humanity to archaeological enquiry.

Detail from Rose Ferraby’s artwork (inside THE SLEEPING PLACE).

I’ve written in earlier posts about the influence of the book Theatre/Archaeology by Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks on the development of my poetic for this book. I want to quote them again in this context. They advocate for a new way of making the archaeological record, including ‘mutual experiments with modes of documentation which can integrate text and image’. They talk about the importance, when coming face to face with the mysteries of the past’s material traces, of creating ‘joint forms of presentation to address that which is, at root, ineffable’ (Theatre/Archaeology, 2001, p 131). For me, addressing the ineffable is able to happen, if anywhere, across the spaces and relationships of THE SLEEPING PLACE’s images, text and design.

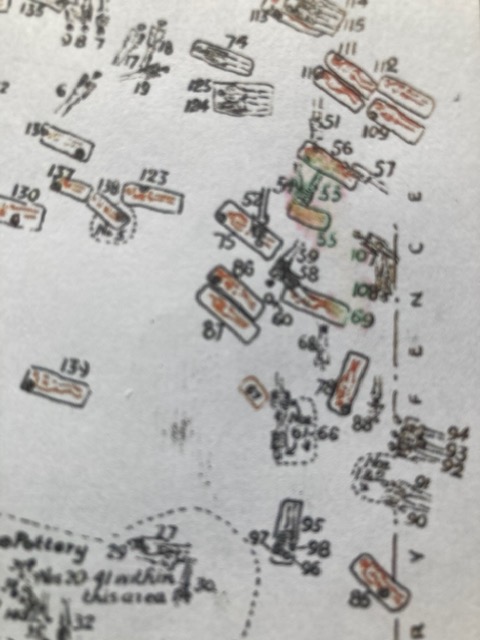

But, at a much earlier stage, it was doodling rather than art which helped me shape THE SLEEPING PLACE. Rather than textual, my first exploratory response to engaging with the archaeological archive was with sketches of lively skeletons dancing across geographical maps and site plans. As these cartoon skeletons increasingly started to resemble letters and words, so the ideas for my textual response emerged.

Skeleton doodles combined with grid and map.

Skeleton doodles playing with how to structure text on the page.

And now these little skeleton doodles have a new role in this project, appearing on my hand signed extracts from the text which will accompany the first purchased copies of the book. As I inscribe each page of the published text with these loose-jointed doodles, they emphasise the open-ended nature of this book and the discovery of more and more skeletons just waiting to be made.